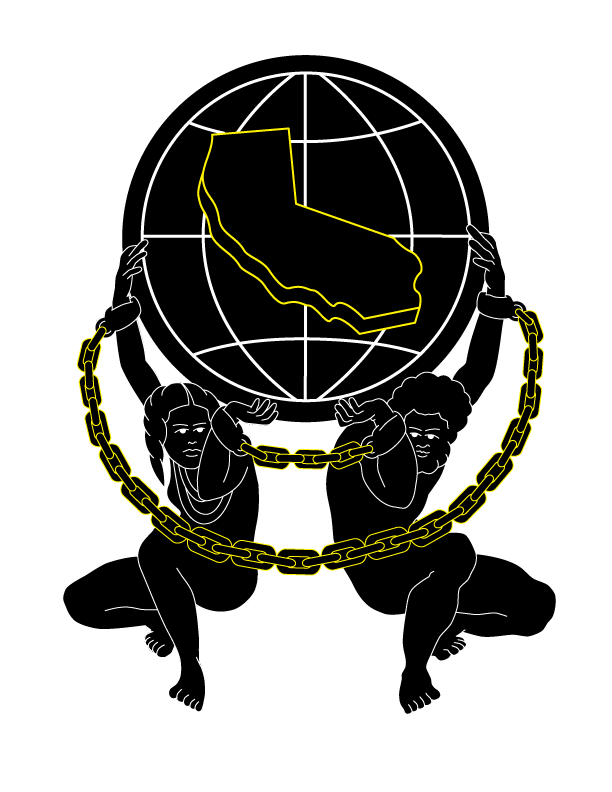

Artwork courtesy of the Tom Feelings Collection, LLC

November 1, 2022 | Episode 3: Act for the Government and Protection of Indians

Tammerlin: [00:00:13] It was cold and raining when George Woodman drove his battered wagon into Ukiah, a small mountain town in northern California. It's bed was sagging between mud covered wheels. Sixteen children were huddled under a pile of wet blankets hidden from view. The youngest was just two years old.

Stacey Smith: [00:00:37] George Woodman is kind of this shadowy figure I would call him. He really got a reputation for being a kidnapper of Native American children. And apparently everybody in Mendocino County knew this. So my name is Stacey Smith. I am an associate professor of history at Oregon State University.

Tammerlin: [00:01:01] A local woman named Helen Carpenter wrote about it. Here's what she said.

Helen Carpenter: [00:01:08] For many months, a few Indian children at a time had been brought down from the mountains on horseback, two or three tied to one horse.

Tammerlin: [00:01:18] But this time, George Woodman showed up with a wagon packed full of children. Some of the townspeople even assisted him as he was on his way to Sonoma and Napa Counties.

Helen Carpenter: [00:01:31] To make them presentable to the outside world. The kind lady of the house provided them with traveling costumes, a single article of dress to the child.

Tammerlin: [00:01:42] One of the children was a little girl named Rosa.

Stacey Smith: [00:01:45] And Rosa probably wasn't her birth name. That's just the name we know her by in the historical record. Probably the only name we know her by. And and I first learned about Rosa from the memoir of this white woman named Helen Carpenter. She had been living in Mendocino County, oh, probably since the 1850s and definitely since the 1860s. And she talks about all of what happens to Woodman, and she also talks specifically about how each child is put into a white household.

Tammerlin: [00:02:27] I'm Tammerlin Drummond at the ACLU of Northern California. And this is Gold Chains, a podcast about the hidden history of slavery in California. If your high school history class was anything like mine, you were probably taught that California joined the union as a free state and never had slavery. Well, that's a lie. California was free in name only.

Stacey Smith: [00:03:02] When we imagine the American West in Western movies, novels and things like that we often think of the West is really this wide open place, a place where individuals are free to move around, to make money and to improve their lives. But a large number of people, including Indigenous people, including enslaved African Americans, were forced into labor relationships away from their homes and away from their families.

Tammerlin: [00:03:35] In other words, the California dream was not for them.

Stacey Smith: [00:03:41] Instead, the wealth of California, the prosperity of California, much of it rested on the backs of people who were not white and not free. And I think that that's a really important story to tell.

Tammerlin: [00:03:59] In this episode of Gold Chains. We look at an early California law that allowed white settlers to enslave Native children. Why does any of this matter today? Well, it's not just old history. Over time, the practice of separating Native children from their tribal communities has taken on many forms. There were the so called Indian boarding schools. Various government sanctioned adoption schemes have funneled Indigenous children into non-Native, mostly white households. And now there's an upcoming Supreme Court case dealing with the very same issue. It's called Brackeen v Haaland and will connect the dots between past and present. Before we go any further, I just want to let you know this episode contains depictions of violence and may not be suitable for small children. When we left George Woodman, he was making plans to sell six Native children. Unfortunately for him, when he drove into Ukiah, the authorities were waiting for him.

Stacey Smith: [00:05:16] Rumors suggest that he had kidnapped roughly 200 children over the course of his entire career. So it wasn't that surprising, probably to many of his Mendocino County neighbors when they heard that he had been arrested.

Tammerlin: [00:05:35] In the 1850s and early 1860s. Men like George Woodman could make a very good living selling Indigenous children all over California.

William Bauer: [00:05:45] The price for Indigenous children varied across the state, but in some instances you might be able to get $200 for a boy, $150 for a girl or something along those lines, because there was a high demand for Indigenous child labor, because most of the people who were coming into California didn't want to work on farms and ranches. They wanted to go off and strike it rich mining for gold. And so what you see is that Indigenous boys were put to work on farms and ranches, tilling fields, planting fields, tending livestock. And then Indigenous girls were kept as domestic servants for these families. My name is William Bauer. I'm an enrolled citizen of the Round Valley Indian tribes of Northern California and a professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. My tribal backgrounds are Wailacki and Concow.

Tammerlin: [00:06:40] Let's take a step back to 1848. At that time, there were about 150,000 Indigenous people in California, and their families had been living on the land for generations. Their world was about to be turned upside down.

Archival Footage: [00:07:00] On the 24th of January, 1848, Jim Marshall, a carpenter, spotted something shiny. It was a nugget of pure gold.

Tammerlin: [00:07:09] And as the news spread, hundreds of thousands of people rushed to California, hoping to strike it rich.

Archival Footage: [00:07:16] They came here from the East Coast and then from Europe and later even from China. They said Just do a little digging and pick up the pieces of gold. In no time you'll be back home with a servant carrying the treasure for you.

Tammerlin: [00:07:29] Before long, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of gold was flowing out of the mines. Eager to cash in. The US Congress fast-tracked California for statehood in 1850. That same year, the state legislature passed a law to appease white Californians who were demanding cheap labor.

Stacey Smith: [00:07:51] The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians was essentially a wide ranging code for Native Americans to live under and allowed white people to regulate their behavior.

Tammerlin: [00:08:08] Local officials could now arrest Native people on trumped up charges like not having a job in a white household or seemingly not having some place to live. Anyone who got arrested had to work for free for whomever paid their bail. The innocuously named Act for the Government and Protection of Indians had an especially evil provision that targeted children. People called it the apprenticeship law.

Stacey Smith: [00:08:36] What the law did is that it said that a white person could go before a court as long as they said that they had gotten the child from the child's, quote unquote, parents or friends, then they could take that child to justice of the peace local law official, and say, hey, I want to have this child made my ward. There was very little that a potential guardian had to do in order to get a hold of these children. And so this was a way that white people could get Native children. For free.

Tammerlin: [00:09:17] And the law allowed them to hold the children captive until they were young adults. Supporters claim the children would be better off in white Christian homes where they could be assimilated into civilized society. In reality, it was legalized slavery.

William Bauer: [00:09:39] I think there's just a common misperception in American history that slavery was particularly like an African American story. Moreover, that slavery is a Southern story, and I think a lot of people are beginning to kind of understand that no, slavery is much more of a kind of a continental story, and it involves an array of other people, including Indigenous people. Also, the enslavement of Indigenous peoples doesn't necessarily look like chattel slavery with large plantations. People at the time don't call it slavery. They call it something else indentured servitude or convict leasing or some of these other things that become almost euphemisms for system that ensnared people in labor relations in which they don't have full control over where they work, what they do, and how they're compensated.

Tammerlin: [00:10:33] Some white settlers were willing to pay a premium to get a toddler.

Stacey Smith: [00:10:39] In their minds, they were investing in future domestic servants who wouldn't have the freedom to. Get away from them. Until they became adults, they. Really thought of this as an opportunity in a free state where slavery was technically illegal. What? These white California settlers did is that they use the law in underhanded ways, sneaky ways to. Bend society to what they wanted. If you don't call something slavery and it has different mechanisms and different types of regulations than slavery, then you can effectively establish slavery without legally calling it slavery.

Tammerlin: [00:11:36] Later on, California officials changed the law so that white people could get custody of any Indigenous child who was an orphan.

William Bauer: [00:11:45] There are stories of mountain men going into California, Indian communities attacking them and then stealing children, for instance. Early in 1861. The superintendent of Indian affairs in California, his name was George Hanson, was traveling in the Sacramento Valley. He comes across a mountain man with about ten children, and he was coming out of the mountains of Northern California. And Hanson says.

George Hanson : [00:12:10] I apprehended three kidnappers with nine Indian children from 3 to 10 years of age, which they had taken from Eel River in Humboldt County. One of the three testified that it was an act of charity to hunt up children and then provide homes for them because their parents had been killed. My counsel inquired, How do you know that their parents had been killed? Because he said I killed some of them myself.

Tammerlin: [00:12:42] Hanson writes regular reports back to Washington about violent attacks on Native people. He blames the act for the government and protection of Indians. So he creates a team of federal agents to hunt down child traffickers. In fact, he's the one who sends Mendocino authorities to arrest George Woodman in Ukiah.

William Bauer: [00:13:05] He was arrested and paid a fine of $100 for trafficking Indigenous children was a slap on the wrist, and he can continue to operate after paying this fine. And here we see the ways in which kind of the legal system of California allowed this system of slavery to exist.

Tammerlin: [00:13:25] After George Woodman gets out of jail, he files a petition in court to become the legal guardian of the very same children that he stole. And can you believe it? A judge actually granted his request.

Stacey Smith: [00:13:39] And so it ends up being a really big courtroom drama in early 1860s Mendocino County. Some of the reaction of the people in Mendocino County to Woodman's kidnapping was, oh, this is horrible. He is killing Native families and taking away their children and he's selling them. This is slavery. California is a free state. The other reaction is that almost 100 white residents of Mendocino County petitioned various legal officials to have themselves appointed as the guardians of these children. They hoped, really, to kind of get a windfall from his arrest. Now, they wouldn't have to pay Woodman for the children. They could just be assigned to the children as their guardians by the court.

Tammerlin: [00:14:37] And while all this is going on, George Woodman writes a letter to the Mendocino Herald.

George Woodman: [00:14:44] I have seen with great pain various attacks against me in the newspaper. I am here and described as a monster, a kidnapper of children. A more damnable lie was never spoken by the lips of a man. I ventured a state that no man was ever more mindful of the duty of benevolence toward this unfortunate race than I have been.

Tammerlin: [00:15:10] He even had the gall to write to George Hanson for his help. That would be the same George Hanson who had Woodman arrested in Ukiah.

George Woodman: [00:15:20] I never have, nor never will take children unless by consent of their parents or chief, except children that are prisoners of war or that are starving and must be protected. Some steps ought to be taken immediately. The children are now like a lot of rats in a hot oven that are to be burned or knocked in the head when they come out. If you will give me the privilege, I will take care of all of the children that the chiefs and the tribes desire me to take and find them homes of the first class.

Tammerlin: [00:16:02] After a number of twists and turns in the case, George Woodman eventually loses his battle for custody of the 16 Native children. Mendocino officials placed them with eager white guardians. Remember the little girl, Rosa? They give her to a woman who we know as Mrs. Bassett, probably a pseudonym. We have no idea what kind of work Rosa did in the household. All we know is that a year later, the little girl was found dead.

Stacey Smith: [00:16:32] And Nobody really knew about it at first, which is curious. The newspaper from the area notes that the county coroner heard a rumor that an apprenticed Native child, a girl about the age of 12, had died on the Bassett family's property.

Tammerlin: [00:16:56] The coroner thought it was suspicious and called a special inquest.

Stacey Smith: [00:17:01] So there's some testimony probably from the Bassett family members themselves who claim that Rosa had gotten into a barrel of whiskey and that she had drunk so much that she became sick and that she was so troublesome in her extreme intoxication that they had locked her out of the house because she was just bothering them too much. And then, lo and behold, she was dead the next morning.

Tammerlin: [00:17:31] Okay. So they locked her out of the house in the middle of a raging snowstorm.

Stacey Smith: [00:17:36] Yes, Rosa. In their minds died of exposure after having essentially drunk herself to death. So that's the story that the Bassett family appears to be telling.

Tammerlin: [00:17:50] But that's not what the coroner thinks.

Stacey Smith: [00:17:52] So the coroner didn't find any evidence of alcohol in the child's system, in her stomach or her intestines. Instead, what he did find was. A severe bruise on her stomach.

Tammerlin: [00:18:12] He said it was evidence that she was beaten with such force that it likely killed her. No one was ever prosecuted. Stacey Smith believes Rose's death can be traced directly back to the apprenticeship laws.

Stacey Smith: [00:18:28] There's no oversight whatsoever. Anything that happens within a white household stays in that white household. And so predictably, perhaps these children really are subject to all kinds of abuse. Many, many of them die in their apprenticeships before they grow up and legally are able to get out of them.

Tammerlin: [00:18:58] It's a hot Monday in August. And William Bauer, you know, he's the historian you met earlier and he's driving into Round Valley, the reservation where he was raised. It's also the place where George Woodman and other traffickers used to hunt Native children.

William Bauer: [00:19:15] Round Valley is located about 150 miles north of the San Francisco Bay area. As the name says, it's a round valley surrounded by mountains. It remains today kind of really rugged terrain, difficult to get to. It's one of these places in California that has one road in, one road out.

Tammerlin: [00:19:32] He passes part of an old fence that he sees every time he returns home to visit his parents. According to his tribe's oral history, white Americans forced Indigenous people to cut down trees and carry heavy poles down into the valley to build this fence.

William Bauer: [00:19:49] And one person was whipped so badly that people remember that he went crazy afterwards. When I drive by the fence, it's this lingering kind of reminder. It becomes kind of a physical symbol of this neglected history of slavery in the Round Valley area.

Tammerlin: [00:20:06] In 1854, the federal government opened a reservation at Round Valley. It was part of a massive campaign to relocate Indigenous tribes from all over California and seize their land.

William Bauer: [00:20:18] And so in the middle of the American Civil War in 1863, the United States rounded up, Concow people from the Sacramento Valley, incarcerated them in a corral outside of Chico, California. And then the Army forcibly marched about 460 Concow people, more than 100 miles from Chico to the Round Valley Reservation. They marched over the mountains where the peak is more than 7000 feet above sea level. And then down into the reservation, almost half of the people perished on the way over.

Tammerlin: [00:20:52] And William Bauer's own great grandfather was one of the survivors. He was only 14 when he got to Round Valley. Once Native people arrived, they were held captive and could not leave.

William Bauer: [00:21:06] And Native leaders would say, no, we don't want to go, because if you're going to concentrate us on the reservation, we're going to be vulnerable to these people who are attacking our communities and stealing our children and selling them throughout the state. So the reservation system could have made Native peoples more vulnerable to the people who were exploiting the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.

Tammerlin: [00:21:26] Meanwhile, the state and federal governments were openly pursuing policies to exterminate Native tribes. California officials offered bounties for Native peoples scalps and state militias went on murderous rampages, attacking Native communities. Kidnappers would come in behind them and sweep up the children. Some of the abducted kids managed to escape and return home.

William Bauer: [00:21:51] One woman remembered that her grandmother died with scars on her back. She was stolen as a child and then abused by the person who purchased her. The woman remembered, quote, They made a slave out of grandma. I was at the National Archives rifling through folder after folder of material related to the Round Valley Reservation. And I came across this letter and there was this woman. She said she was Yuki from Round Valley. And I believe that this letter was dated in the early 19 teens or something along those lines. And she writes the agent at the Round Valley Reservation, and she says, I was stolen as a child and I'm living in Arizona and I want to make connections back to the reservation. And on one hand, it was a very kind of powerful story because people kind of survive this practice. They survive well into kind of later in their lives. But for me, it made me think that she remembered living and growing up in Round Valley and really wanted to kind of make efforts to get back there. And unfortunately, I never found if the agent responded to her or if she was able to make it back to the reservation. But those connections, those ties to home and to place were never completely obliterated by this system of slavery that existed in California in 1865.

Tammerlin: [00:23:10] In 1865, the so called apprenticeship laws were finally repealed. That's the same year the Civil War ended.

Stacey Smith: [00:23:17] I guess it finally dawned on them that killing Native families and taking Native children was not a way to have peaceful relations with Native peoples in the area and that Native people would actually come into the settlements and look for their children, or that they would take revenge against people who had kidnapped their children and that it was creating violence and chaos in the towns. And so more and more white settlers turn against apprenticeship. We have at least a couple accounts of Native children who are apprentice to white families being shot down by other white settlers as they're working in the fields. Little kids who, because they are Native and because their presence is deemed to be a threat to the white community, even if they are tiny babies in. White households that they have to be eradicated.

Tammerlin: [00:24:20] And they're just standing in the fields.

Stacey Smith: [00:24:23] Yeah, I know. It's extremely heavy. It makes me sick to my stomach to talk about what happened in Northern California in the 1850s and 1860s. And I'm seeing that even as somebody who has read these court records and written about these incidents for. 20 years now. The horror of what happened in California, the genocidal violence against Native people, and especially the enactment of that violence against children. Is unfathomable.

Tammerlin: [00:25:03] The apprenticeship laws may have ended, but the forced separation of Indigenous children as a tool of US expansionism and conquest that was just beginning. In the late 1800s, the federal government began ramping up the Indian boarding school program. Their motto Kill the Indian. Save the man.

William Bauer: [00:25:26] School officials believe that if they brought Indigenous children into these schools far from their homes and their parents, Native children would unlearn their, quote unquote, savage ways and become civilized.

Tammerlin: [00:25:38] All of the Native children living on reservations were forced to attend these militarized institutions.

Tedde Simon: [00:25:44] Federal Indian agents would come into tribal communities and in many instances, quite literally, take children from their parents arms. Some kids would know where to go to run and hide behind a bush or under a rock or in the trunk of their family's car because they didn't want to be taken. This is Tedde Simon. I'm the Indigenous justice advocate at the ACLU of Northern California and a citizen of the Navajo Nation. There was a lot of resistance to the stealing of children, and the government's response was often violent and often brutal. People were imprisoned for refusing to allow their children to be taken to these schools.

Tammerlin: [00:26:30] Federal officials also threatened to cut off their meager reservation rations, which was their only source of food. The US government operated many of the boarding schools. Others were run by churches. Converting children to Christianity was part of the master plan to deprogram them.

Tedde Simon: [00:26:48] When they arrived, their hair was immediately cut, Their clothes were taken and they were given new English names. And abuse was rampant at these schools Sexual, physical, emotional, spiritual abuse and that kind of brutal corporal punishment for things as as simple and as basic and as human as speaking your own language.

Tammerlin: [00:27:12] The so called schools rented kids out to neighboring white farmers as cheap labor, a throwback to California's early Indigenous child slavery law.

William Bauer: [00:27:24] During the Great Depression. My grandmother attended the Stuart Indian School, which is located in Carson City, Nevada, and the Sherman Indian Institute, which is located in Riverside, California. And so Riverside, I think is about 600 miles from the Round Valley area.

Tammerlin: [00:27:38] William Bauer doesn't know much about his grandmother's time at the boarding schools.

William Bauer: [00:27:43] When I asked her about her boarding school experience, that was one thing that she really did not want to talk about. I later discovered in a letter that she wrote to her father that she did not like the school and wanted to come home as quickly as possible.

Tammerlin: [00:27:58] One of the schools she attended, the Sherman Institute, was notorious for abusing the children. It had a cemetery attached to it.

Tedde Simon: [00:28:07] We know that there's one at Sherman because it is marked. And in fact, every summer a group of people go to remember to clean the graves and to be present with the children who are buried there.

Tammerlin: [00:28:21] Sherman wasn't the only Indian boarding school with the cemetery across the United States, 53 burial sites have been found at former Indian boarding schools. Children died of neglect and physical abuse.

Tedde Simon: [00:28:37] Many times, their families didn't know that their children had died at these schools and these children's bodies were not returned home. So they didn't go through proper ceremonial burials and never had the opportunity to be returned to their homelands.

Tammerlin: [00:28:55] Teddy Simon's great grandmother was also sent to Sherman after being shipped to another Indian boarding school in Colorado.

Tedde Simon: [00:29:03] Boarding schools themselves were in many ways incredibly effective at what they were created to do, which was to erase people's Indigenous identity and traumatize people from ever wanting to be Indigenous again, to speak their Native languages or return home to their homelands or have a connection with their family and their kinship networks. My great grandmother did not speak Navajo once she left the Indian boarding schools. My sister and I are actually the first people in our family since our great grandma Cora to try to learn to speak Diné Bizaad. And you know, it's our generation who is coming back to learn more.

Tammerlin: [00:29:52] Most of the schools shut down in the 1970s or were transferred to tribal control. But as that era was ending, the federal government created a new program.

Tedde Simon: [00:30:03] Called the Indian Adoption Project, specifically with the goal of taking Native children from their homes, especially on reservations and adopting them into white middle class families where they would be assimilated into dominant culture and Christianized.

Tammerlin: [00:30:21] Under the Indian Adoption Project. Christian churches put children in residential institutions where they were later adopted out. Thousands of Navajo kids were sent to live in Mormon homes and work on farms. Between 1941 and 1967, more than a third of all Native children in the United States had been separated from their families.

George Hanson : [00:30:45] Thanks to decades of organizing and advocacy by Indigenous leaders calling attention to the crisis of Indian child removal, Congress began an investigation in the early seventies.

Archival Footage: [00:30:59] Several hundred.

Archival Footage: [00:31:00] Indians and their supporters walked.

Archival Footage: [00:31:02] From the Lincoln Memorial, past the Washington Monument up to.

Archival Footage: [00:31:05] Capitol Hill today. Their destination after a cross-country walk all.

Archival Footage: [00:31:09] The way from California.

Archival Footage: [00:31:11] We want our children and our grandchildren, but we.

Archival Footage: [00:31:13] Are not allowed to keep them.

Tedde Simon: [00:31:15] Often, Native children were removed from their families not because of real physical abuse or really anything to do with the well being of the children, but based on biases and cultural insensitivities, like people living in multigenerational families.

Tammerlin: [00:31:33] So in 1978, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act, known as ICWA.

William Bauer: [00:31:40] The Indian Child Welfare Act was implemented in order to empower tribal governments to have more say over how and when Indigenous children were being adopted.

Tammerlin: [00:31:50] The law says that every effort must be made to place the child in a Native home if a family member isn't available. And if that's not possible, then a non Native family can adopt.

Tedde Simon: [00:32:03] Understanding that it's in the best interest of Native children to grow up with a connection to their culture and their language and their heritage.

Tammerlin: [00:32:12] The law isn't perfect, but it has helped keep more Indigenous children in their tribal communities. But now the Indian Child Welfare Act is under attack.

Archival Footage: [00:32:25] The United States Supreme.

Archival Footage: [00:32:26] Court is going to hear a lawsuit this fall to challenge and potentially declare the act unconstitutional. The case is.

Archival Footage: [00:32:33] Known as Brackeen versus Haaland.

Archival Footage: [00:32:35] And tribes worry it could have implications for the future of their sovereignty.

Tammerlin: [00:32:40] The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments on November 9th. So how did we get here? Well, it's complicated. In 2016, Jennifer and Chad Brackeen became foster parents to a ten month old Navajo boy.

Tedde Simon: [00:32:59] So the Brackeens are a white evangelical, upper middle class family in Texas.

Tammerlin: [00:33:05] They wanted to adopt the boy, but they encountered obstacles. Because of ICWA, child welfare workers decided to place the child for adoption with an Indigenous couple. But the Brackeens went to court and eventually got custody. Then they became foster parents to the boy's half sister, and now they want to adopt her as well. So they've joined six other foster parents and the state of Texas in suing the federal government.

Archival Footage: [00:33:34] They claim that the Indian Child Welfare Act, or ICWA, which prioritizes Indigenous communities in the placement of Indigenous children, is racist against white people.

Tammerlin: [00:33:43] And they want the Supreme Court to rule the law unconstitutional.

Tedde Simon: [00:33:49] If the Supreme Court overturns the Indian Child Welfare Act, it would have devastating consequences for Native children and families and tribes and also really threatens the underlying laws that protect tribal sovereignty. All of those would be on the chopping block.

Tammerlin: [00:34:07] Tribal nations, civil rights organizations and many others have joined the legal fight to defend ICWA. The ACLU filed an amicus brief in the case asking the Supreme Court to uphold the constitutionality of the law. Tribal nations argue that big industry and conservative interests are using this child custody case as a means to ultimately dismantle tribal sovereignty altogether. Why? Because a lot of the land controlled by Native American tribes has valuable resources on it, like oil and coal, that multinational companies want free reign to be able to exploit for profit.

Tedde Simon: [00:34:51] The ACLU is involved because this is a critical issue for the survival and existence of tribes and of Indigenous people as Indigenous people in this country.

Tammerlin: [00:35:04] The Brackeens argue that the Indian Child Welfare Act actually hurts children by forcing them to unnecessarily languish in foster care. They also claim they can take better care of the little girl.

William Bauer: [00:35:18] Indigenous families become stereotyped as being inadequate, as being incapable of taking care of their orphaned kin because of allegations that all Indigenous families are impoverished, that Indigenous peoples are somehow alcoholics.

Tammerlin: [00:35:34] Historian William Bauer sees a through line between the Brackeen case all the way back to California's act for the government and protection of Indians that ensnared Rosa.

William Bauer: [00:35:46] If the children are taken from their lands and enslaved in a household in Arizona or Indigenous children are taken to a boarding school, or if Indigenous children are then adopted out of their families and into non-Native families elsewhere in the United States, then Indigenous people are not on their homelands, and if they're not on their homelands, then it becomes a justification for the United States to take those lands. And I think cruelly these policies are often said to be in the best interests of Indigenous children.

Tedde Simon: [00:36:18] It's a story that impacts every Native person in this country. But if we don't talk about it, if we don't teach about it, if it's not in our public school education or our textbooks, then we can sweep all of that under the rug and pretend like it never happened and not deal with that legacy as a country.

Tammerlin: [00:36:48] You've been listening to Gold Chains, a production of the ACLU of Northern California. I'm your host and writer, Tammerlin Drummond. Joanne Jennings is our senior producer and editor. And Renzo Gorrio created the mix and original score. Our executive producer is Candice Francis. We'd like to thank our wonderful guides, Stacy L Smith, William Bauer, and Tedde Simon. Our associate producers are Lisa P White and Carmen King. A special thanks also to our voice actors Pauline Shindler, William Freeman and Avi Frey. Elise Manoukian provided fact checking and production assistance. The old recording was done by Julie Conquest, Ron George and Eric. We'd also like to thank the following members of our gold chains Team Brady Hirsch, Gigi Harney and Eliza Wee. We thank also want to Abdi Soltani, executive director of the ACLU of Northern California. A special thanks to World Affairs. Oregon State University and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas for providing us with recording studios. Archival sound was provided courtesy of Periscope Films and Prelenger Archives Visit Gold Chains The Hidden History of Slavery in California at goldchainsCA.org. It includes links to our guests in this episode and to other narratives. If you like what you've heard, please rate it wherever you listen and spread the word. Thank you for listening.

The mission of Gold Chains is to uncover the hidden history of slavery in California by lifting up the voices of courageous African American and Native American individuals who challenged their brutal treatment and demanded their civil rights, inspiring us with their ingenuity, resilience, and tenacity. We aim to expose the role of the courts, laws, and the tacit acceptance of white supremacy in sanctioning race-based violence and discrimination that continues into the present day. Through an unflinching examination of our collective past, we invite California to become truly aware and authentically enlightened.