California, a "Free State" Sanctioned Slavery

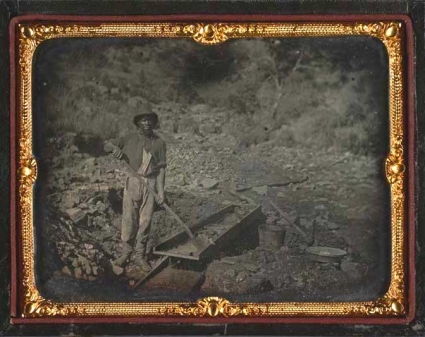

Credit: Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

In a late-night raid in April 1852, three formerly enslaved black men who had built a lucrative business hauling mining supplies during the California Gold Rush, were rousted from their cabin by armed white men. They were forcibly taken before a justice of the peace in Sacramento County who ordered them deported to their former “owner,” a white man in Mississippi.

Robert Perkins, his brother Carter, and their business partner Sandy Jones, would file the first lawsuit challenging the state’s new Fugitive Slave Law. Passed just 6 weeks earlier, it decreed that any enslaved black person who had entered California when it was still a territory had no legal right to freedom even though the state constitution banned slavery.

According to the U.S. history most of us are familiar with, California came into the Union in 1850 as a “free state.” Slavery was an evil that occurred in the south, far from here, or so we were taught. Yet famed for its liberal reputation, California has a far more complicated history.

In 1848 when the gold rush hit, white southerners flocked to the state with hundreds of enslaved black people, forcing them to toil in gold mines, often hiring them out to cook, serve, or perform a variety of labor. Sometimes fortunes were amassed on the backs of this free labor. Yet California’s place in the nation’s history of slavery is missing from most historical accounts and many are surprised to learn of its practice in the golden state.

Like the nation it became part of, California was mired in contradictions from its beginning. It was a free state born out of the politics of slavery. In a precarious effort to balance the concerns of Southern slave-holding interests and those against slavery’s expansion, Congress cobbled together the Compromise of 1850. The series of bills admitted California as a free state, while also granting important concessions to the South. That included the draconian federal Fugitive Slave Act, which required government officials and ordinary white citizens in all states and territories to actively assist slaveholders in recapturing enslaved people who escaped from slave-holding jurisdictions.

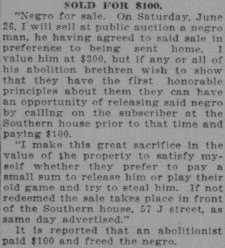

California’s constitution proclaimed that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for punishment of a crime, shall ever be tolerated.” Yet archives statewide contain evidence that slavery was practiced out in the open. One newspaper ad in the Sacramento Transcript offered “A valuable Negro girl, aged eighteen…of amiable disposition, a good washer, ironer and cook” for sale.

Yet as the Perkins case illustrates, many blacks struck for freedom. In response, the pro-slavery legislature passed a fugitive slave law, specifically targeting blacks who escaped in California and had not fled from slave states.

The Perkins brothers and Sandy Jones were the first test case.

In 1849, Charles Perkins, a white man from Mississippi set out to mine gold in Placerville County, taking Carter Perkins, an enslaved man on his father’s plantation with him. Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones soon followed, forced to migrate west and leave their wives and children behind. All three went to work for Charles Perkins mining gold.

When Charles Perkins fell on hard times and decided to return South, he could only afford the return passage for himself. He left the three black men with a friend. He in turn agreed to grant them their freedom if they worked for him for six months. Set free in November 1851, the industrious trio launched a mining supply business in Ophir, earning $3,000 (close to $100,000 in today’s dollars)

Their California dream came to an end when Charles Perkins reported the men as runaway slaves and demanded their return.

Sacramento’s activist black community raised funds to hire Cornelius Cole, a prominent lawyer and founder of California’s Republican Party which opposed slavery’s expansion, and future U.S. senator, to defend the former miners. Cole argued that the state Fugitive Slave Law violated the California constitution’s slavery ban.

However, in 1852, the pro-slavery state Supreme Court ordered the defendants remanded to Charles Perkins in Mississippi. Legend has it that they escaped during their ship’s passage through the Panama isthmus, but their fate is unknown.

As evidenced in the Perkins case, the persistence of slavery was met by African American resistance. Newspapers covered street brawls between enslaved people and those who claimed to own them. In the gold mines of the Sierra Nevada, on the wharves of San Francisco, on downtown streets in Los Angeles, on farms and ranches throughout rural counties, and in courtrooms, the drama of slavery and resistance to slavery played out in California during the state’s formative first decade. Some prominent African American leaders even went armed into isolated areas and liberated slaves.

In an effort to highlight this omission from the historical record, the ACLU of Northern California, KQED, the California Historical Society, and the Equal Justice Society partnered on a unique public education project, Gold Chains: The Hidden History of Slavery in California. It features multimedia stories and archival research that examine this little-known history that was instrumental in shaping California’s complex racial landscape today. The history unearthed by the Gold Chains project adds to our understanding that no part of the United States – including California – was untouched by the pernicious system whose legacy manifests today in our laws, courts and culture.

Susan D. Anderson is the Director of Public Programs at the California Historical Society.