Cops Complain about Being Tracked on Waze: “Do as We Say, Not as We Do”

Page Media

Do you have the right to tell others that you saw an on duty cop in public? According to law enforcement in two Associated Press articles this week, the answer is “No.”

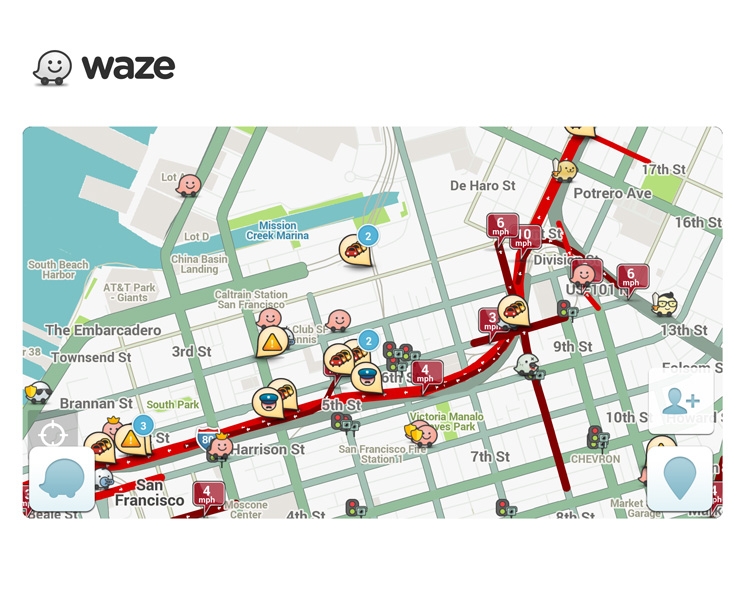

At the center of these reports is Waze, a popular navigation app that allows users to share information about the location of police cars along the road in addition to other useful information about accidents, traffic, and even construction zones. Officers are asking Waze’s parent company, Google, to shut down the police-tracking feature in the app. But talking about the police in this way is protected speech, and Google should refuse to censor it.

The freedom to talk about what our government is doing is one of the most important rights protected by the First Amendment and the California Constitution. In fact, courts have already tackled essentially the same issue that Waze raises, ruling that the Constitution protects your ability to inform oncoming drivers about speed traps by flashing your headlights. Using technology that allows us to communicate more effectively, whether it’s to record interactions with the police or to warn others about the location of aggressive raids, illustrates the value of this protection, rather than providing a reason to undermine it. Given the strong protections that our laws rightly place around freedom of expression, claims that using Waze to tag police sightings may be illegal make little sense.

It’s hard to reconcile many of the arguments law enforcement officials are raising about Waze, given their tendency to brush aside privacy concerns about local surveillance, with the claim that we have no expectation of privacy in public spaces. To cite just one example, many police and sheriffs’ departments use license plate readers to collect the locations of drivers in a community, retain that information for years, and even place it into databases shared with other localities and the feds. And that information has been and will be misused, be it to monitor congregants at mosques or to track other lawful activity. Before the government seeks to eliminate its public movements from Waze, it should consider whether the same arguments apply to its own tracking programs.

The public has the right to talk about public servants serving in public. This means you can talk about the police on Waze, WhatsApp, or even via Snapchat selfies taken with your friend the neighborhood cop. As technology moves forward and places powerful new tools in our pocket, we do not lose our constitutional right to speak about the police, whether we are documenting an unlawful arrest or just notifying other motorists about speed traps. Unfortunately, government demands to kill apps about law enforcement have succeeded before. While Google has resisted these calls so far, we hope it continues to do so and that this tool remains available to assist citizens in overseeing the activities of public servants.

Matt Cagle is a Policy Fellow with the ACLU of Northern California’s Technology and Civil Liberties Project.