Exploring the ACLU News Archive: Korematsu v. United States

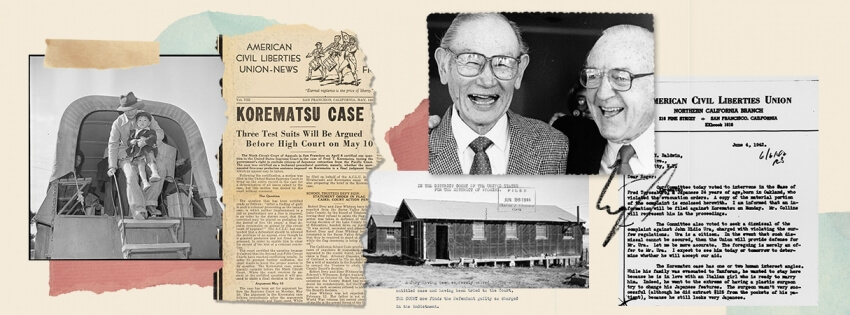

Thanks to a partnership between the ACLU of Northern California and the California Historical Society, every issue of the ACLU News has been digitized and is now available to read online. This blog is the first in a series that examines the archive’s contents.

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent in “relocation centers” across the western U.S.

The order rubber-stamped blatant discrimination, ripping apart families, livelihoods, communities. It took advantage of, and stoked, racist and xenophobic fervor. Eventually, its distorted logic was deemed acceptable by the highest court in our land.

In Korematsu v. United States (1944), the Supreme Court deferred blindly to the military’s claim that a person’s Japanese ancestry marked them as a potential national security threat, authorizing their mass exclusion from society.

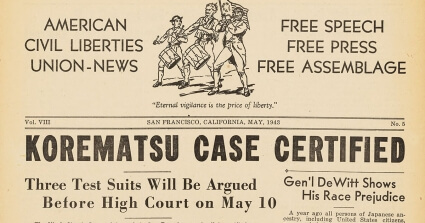

Documentation of the Korematsu case arises throughout the archive of the ACLU News: the member newsletter of the ACLU of Northern California that has been in circulation since 1936, and that documents ACLU advocacy and its historical context.

Like any good historical record, it demands examination in light of the present day. Here, we take a closer look at its reporting on Roosevelt’s incarceration orders and related ACLU advocacy.

Documenting Korematsu

The Korematsu case looms large in this affiliate’s historical record because representatives of this organization brought that suit before the courts. Ernest Besig, the long-serving executive director of ACLU NorCal, met with Fred Korematsu as he sat imprisoned in San Francisco for having refused to evacuate to a Japanese detention center. Together, they decided to challenge the constitutionality of the evacuation order.

It was the Korematsu case that almost broke the bond between this affiliate and ACLU National: Roger Baldwin, ACLU National’s executive director, pressured Besig to drop the case after National’s board issued a policy barring challenges to Roosevelt’s executive order in the belief that backroom diplomacy with government officials presented the best opportunity for advocacy. Besig refused. The case went forward. ACLU National relented.

The ACLU News dedicates significant attention to every twist and turn in the case, conveying this affiliate’s devotion to its representation of Korematsu and the imperative question he forced the American judiciary to consider: Does the Constitution allow for the mass exclusion of people based on their race and ethnicity?

The first mention of the Korematsu case arrives in the July 1942 edition of the ACLU News, in an article that carries snapshots of the bigotry Korematsu fought against before his name became synonymous with one of the most unjust Supreme Court rulings in history.

“The San Francisco case involves 23-year-old Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, who failed to evacuate from San Leandro,” the article says. It explains that, because Korematsu had been rejected from the draft due to stomach ulcers, he had been contributing to the World War II effort on the home front by working as a shipyard welder. But the welders’ union cut short his participation when it “cancelled his membership because of his race.”

Several weeks after Roosevelt issued his executive order, the military created an “exclusion zone” along the West Coast for people of Japanese ancestry. Afterward, the military forcibly removed tens of thousands of people to “assembly centers”: remote, inland incarceration camps where people lived in brutal conditions under the surveillance of armed guards.

Korematsu tried to escape his own forced removal by passing as white. According to the ACLU News, he “hoped to escape detection by having a plastic operation performed on the bridge of his nose and by changing his name.” But the FBI arrested him. He was “placed in the San Francisco county jail, and charged with remaining in a military area from which all Japanese had been ordered to evacuate.”

Through the archive, we can track the journey of Korematsu’s case: from its District Court briefing; to the appeal of the District Court ruling finding Korematsu guilty of violating the military’s evacuation orders; to the U.S. Attorney’s attempts to dismiss the case; to the Ninth Circuit’s ruling “upholding the constitutionality of the Military’s evacuation of all Japanese from the Pacific Coast”; to the shameful Supreme Court ruling.

Contextualizing Korematsu

The February 1944 edition of the ACLU News (published the same month that Korematsu was filed at the Supreme Court) contains a small article on page 3 with the story of a “Mrs. June Arrii Terry.” Terry, of Japanese ancestry and born in Martinez, Calif., had returned home on a military permit with her two-year-old son.

The day after she, her son, and her white husband moved into their house in Martinez, a neighbor named Mrs. Williams stopped by to visit. When Williams “learned that Mrs. Terry was of Japanese ancestry,” she “tried to pull her out of the house.”

The encounter left the Terry family shaken. The article notes that Terry’s husband stayed home from work, the family “kept their blinds drawn,” and they did not dare venture outside to retrieve their furniture from storage.

Williams’ sense that Terry’s Japanese ancestry meant she deserved to be violently extricated from her own home is not so shocking when read in light of the evacuation orders, or in the shadow of the Korematsu ruling. Williams’ actions illustrate how the racism and xenophobia of the Korematsu ruling was replicated in communities across America.

Nor is it so shocking when read in light of the ACLU News articles that document the racism of California’s long-serving attorney general, U.S. Webb. In the July 1942 edition (the first edition to mention Korematsu) he is reported to have testified in support of a lawsuit aimed at disenfranchising Japanese-American voters in San Francisco, with the larger aim of disqualifying vast amounts of Asian Americans from citizenship:

Former Attorney General U.S. Webb appeared before the U.S. District Court on June 26 and declared, “This is a white man’s country, and is yet a white man’s government, if the laws be properly construed.”

The courts struck down the case.

Investigating Tyranny

Coverage of the evacuation orders and their context intensifies in the August 1944 edition of The ACLU News, in which Besig reports on his July 1944 investigation into conditions at the Tule Lake Relocation Center: the largest of the 10 incarceration camps managed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the federal agency charged with overseeing the camps. This camp, situated in the remote northeast corner of California, was designated for the incarceration of people whom the government had deemed “disloyal.”

In the newsletter, Besig details the darkness he and his secretary encountered there. They discovered that, for over eight months, authorities had shut people away in the stockade (the prison within the prison) without trial or hearing. The number of people in the stockade had once numbered 300; at the time of their visit, there were 18.

Besig learned that people in the stockade had “been denied all visiting privileges.” He “heard of men who had never been permitted to see children born after their detention,” and family members who “became sick with grief over the forced separation….”

The article suggests that, as Besig’s investigation deepened, further allegations of abuse emerged. He writes of evidence that internal security police “dragged certain Japanese into the administration building and beat them with baseball bats.” He reports that personnel “who came to work in the administration building the next morning… found a broken baseball bat, and had to clean up a mess of blood and black hair.”

His discovery apparently prompted camp authorities to cut the investigation short. After spending two days at the camp and interviewing a fraction of the people who had requested interviews, armed guards escorted the ACLU NorCal representatives from the premises. They later discovered that someone had poured salt into their gas tank, severely damaging their car.

Besig submitted a complaint to the WRA, and an ACLU NorCal attorney held a conference with WRA officials about the investigation. The ACLU News reports that, subsequently, the WRA “very quietly released” those imprisoned in the stockade.

Looking Back to Look Forward

America now faces a dramatic rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, sparked in part by a presidential administration that employed anti-Asian rhetoric—aimed at China and Chinese Americans, specifically— to divert attention away from its utter mismanagement of a global pandemic that has disproportionately impacted communities of color.

The briefest look at American history shows us that this pattern of racist and xenophobic scapegoating is nothing new. Though today marks 79 years since Roosevelt’s infamous executive order, we recognize the continued ease with which those in power can “other” a vast amount of people with impunity and strip them of rights, protection, and connections to community.

Through the acknowledgement of history, we hold the power to move beyond this cycle. We cannot advocate for better policies or dismantle systems of power without knowing their historical context or their results. The ACLU News archive, now in the public record, stands as a contribution to this effort of memorialization.