Opinion: Courageous Hero Inspires America to Become More Beautiful

Page Media

The following was originally published in the Daily Journal.

I did not expect to sing "America the Beautiful" along with nearly 1,000 people at a recent memorial for Fred Korematsu, a true American hero who died March 30.

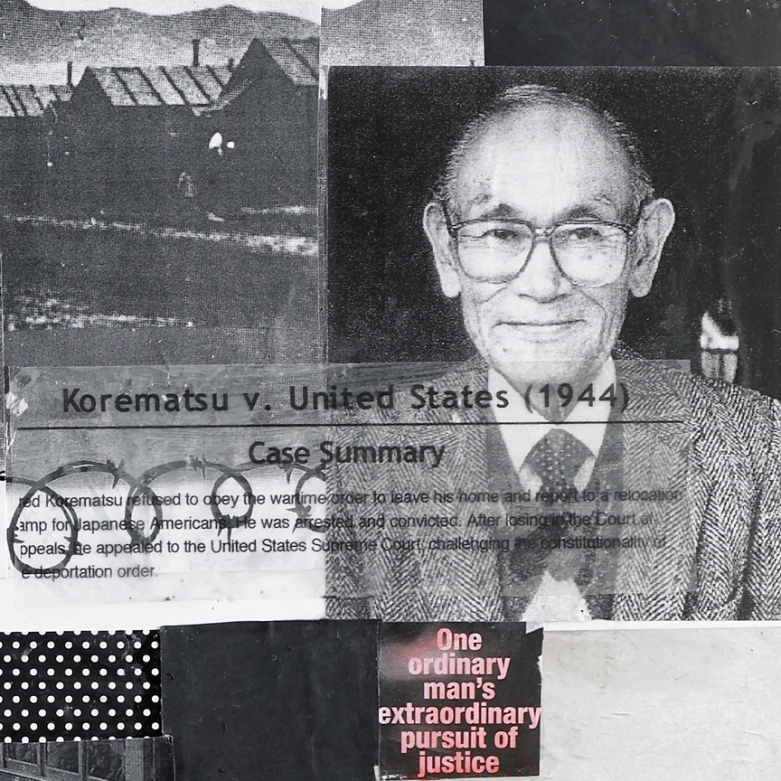

It did not occur to me that this patriotic standard would be fitting for a man who defied the World War II executive order sending Japanese Americans to concentration camps. An American citizen who was vilified and imprisoned in his own country - first in prison for his defiance and later in an internment camp where he was sent without any evidence that he was a danger to this country. Fred Korematsu - like 120,000 other Americans of Japanese descent - was imprisoned solely because of his race.

It must have been a painfully lonely time for Korematsu, his family and friends shipped off to places that hardly would conjure up the majesty of purple mountains. The camps were scattered throughout the western United States - from dusty Topaz, Utah, to the swamplands of Rowher, Ark. - leaving the 22-year-old welder with literally no one to call for help as the headlines blared: "Jap Spy Arrested in San Leandro."

While in jail, a stranger came to his aid. Ernest Besig, the executive director of the ACLU of Northern California, read about a young Japanese American who had been arrested by police on an East Bay street corner, handcuffed and thrown in jail. Besig visited him and offered to post bail and lend his support and legal assistance.

The ACLU of Northern California agreed to represent Korematsu in 1942, a decision that was intensely controversial inside and outside of the organization. The case, challenging the constitutionality of the executive order that allowed the military to summarily exclude Japanese Americans en masse from the West Coast and eventually imprison them, ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The high court ruled 6-3 against Korematsu in 1944. Law students still study that infamous decision upholding the Roosevelt administration's action as necessary for wartime security, and it remains a stain upon the nation's commitment to justice.

Korematsu's courageous decision to defy Executive Order 9066, and his stinging defeat in the U.S. Supreme Court, were memories he and many other internees wanted to put behind them. It wasn't until the movement for redress emerged in the late 1970s as a politically viable issue that the Japanese American community, along with other civil rights supporters, began to question the government's World War II treatment of Japanese Americans and to shine light on the relevant lessons of that injustice.

In that new political atmosphere, law professor and historian Peter Irons, and researcher Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, discovered hidden documents in the National Archives. These documents proved that wartime military officials not only lacked any evidence of Japanese American disloyalty, but rather, that the government deliberately concealed and destroyed evidence to the contrary in an effort to give the U.S. Supreme Court the impression that the wartime exclusion and internment were a "military necessity."

In 1982, Peter Irons shared his discovery with Korematsu and asked the former internee if he would be interested in reopening his case. Korematsu carefully read the documents, and responded in a soft but strong voice, "They did me a great wrong." He agreed to seek vindication.

Korematsu's decision to leave his quiet suburban life, where hard work and commitment to family and community were his focus, and to re-enter the political and judicial fray around Japanese American internment motivated a team of young attorneys, many of whom were sons and daughters of internees. These creative young lawyers crafted a legal strategy using a rare legal procedure, a writ of error coram nobis, to ask a federal judge to vacate Korematsu's criminal conviction for refusing to obey the internment order.

On Nov. 10, 1983, some 40 years after his imprisonment, U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel announced to a packed San Francisco courtroom that she was vacating Korematsu's conviction. In issuing her ruling, Patel acknowledged that the government's actions against Japanese Americans were based "on unsubstantiated facts, distortions and representations of at least one military commander, whose views were seriously infected by racism."

A tearful crowd, many of whom had been imprisoned in America's concentration camps during World War II, greeted Patel's decision, rendered directly from the bench, with joy and disbelief.

When Korematsu stepped out of Patel's courtroom on that autumn day, he was surrounded by reporters. He spoke in a clear and simple manner about fairness and the relief of at last being vindicated. It is a message he would deliver many times to many audiences as he criss-crossed the nation during the next 25 years. Korematsu became a powerful leader in the redress movement of the 1980s, which secured legislation, signed by President Ronald Reagan, that provided for an official governmental apology as well as symbolic financial restitution to former internees.

Korematsu taught a whole new generation about the government's misdeeds during World War II, and the impact it had on the Japanese American community. As Eva Paterson, president of the Equal Justice Society, said, "He served as a reminder that wrongs can be righted. Momentary defeat followed by ultimate triumph is what Mr. Korematsu meant to me."

Korematsu's story of courage has inspired a new generation of lawyers and activists. By standing up against the treacherous collusion of racism, national security and unaccountable government power, Korematsu changed this nation. As explained by Dale Minami, one of the lawyers who represented Korematsu in the coram nobis proceeding, Fred Korematsu was the Rosa Parks for a generation of Asian Americans.

Perhaps no single action by the government represents a greater breach of civil liberties in our nation's history than the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. There was a period of time when we thought this could never happen again. And then came Sept. 11, 2001.

In the aftermath of 9/11, our government launched a series of actions that have violated civil liberties - holding prisoners without charges and engaging in torture at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, rounding up and questioning tens of thousands of young men based solely on their national origin, issuing no-fly lists at airports and engaging in surveillance of library records.

But for the education that has taken place over the last quarter century, the public outcry over these violations could have been greatly subdued. For in 1942, the ACLU stood virtually alone in its condemnation of the government's action. Today, scores of organizations stand shoulder-to-shoulder in fighting effectively against these abuses; nearly 400 communities in every state have passed resolutions calling for limiting the reach of the USA Patriot Act.

And last year, when the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed the issue of the government's current abuse of power at Guantanamo Bay, it had the benefit of an influential brief filed on behalf of Korematsu telling his own story in the context of this country's long history of violating civil liberties in times of national crisis.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton bestowed the Medal of Freedom, this nation's highest civilian honor, to Korematsu for his courage. The proclamation delivered by Clinton stated, "In the long history of our country's constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls ... Plessy, Brown, Parks. ... [T]o that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu."

Korematsu's life and the lessons he taught us remind us of the fragility of civil liberties and the potential for political movements, with activists and lawyers working together, to vindicate our rights. And at the close of Korematsu's memorial, a quartet of trumpets etched his memory in our hearts as they rang out with Aaron Copland's "Fanfare for the Common Man." They reminded us that under these spacious skies, a very patriotic American once stood hopelessly alone, but the simple justice embodied in his singular act of courage eventually drew us and our nation to stand with him.

Dorothy Ehrlich is a former executive director of the ACLU of Northern California.