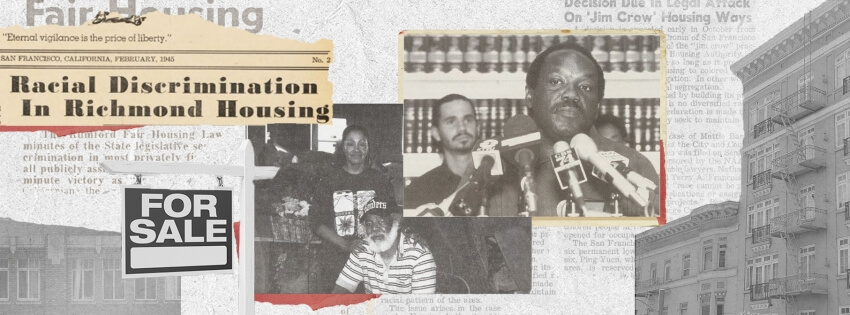

Exploring the ACLU News Archive: The Fight Against Housing Discrimination in California is a Story of Progress and Backlash

In 1945, Ms. W. Whitby, a Black woman working in the Richmond shipyards as part of the war effort, came back from a trip to her mother’s to find the door to her war housing dormitory apartment padlocked shut. She had just separated from her husband and was planning to have her three children and mother come live with her.

Ms. Whitby was new to the dormitory. Not long before she moved in, the Richmond Housing Authority, who managed the apartments, had finally been forced by civil rights advocates to open its doors to Black women. Despite the order, the housing authority was intent on limiting the number of Black tenants, and where that failed, segregating and harassing them, with the hopes of driving them out.

As one of the first Black women to move into the dormitories, Ms. Whitby was a prime target. When she was away, officials conspired to illegally evict her, arguing that as a single occupant, she was no longer eligible for housing even though she had already moved in and paid rent.

The racism that Black residents at the shipyard dormitories like Ms. Whitby faced didn’t stop with those who managed the apartments. Black families also had reason to fear their white neighbors. Earlier that month, a white man had shot a Black child on dormitory grounds, allegedly because they had a disagreement over hot water.

For people in Ms. Whitby’s situation, finding alternative safe housing was not easy. The real estate market was filled with racial housing covenants: contracts written into deeds forbidding future owners from selling to, renting to, or at times even letting Black people onto their property. As Ms. Whitby’s case shows, public housing wasn’t much better. The San Francisco Housing Authority, for instance, kept tightly segregated facilities and only allowed Black people to live in one low-income building.

The ACLU News archive, dating back to 1945, documents the various forms of legalized housing discrimination leveled at Black people in Northern California, and also charts severe backlash to progress, whenever it was made. It provides a snapshot of the ways that businesses, the state, and individuals partnered to exclude Black people from the accumulation of wealth through dispossession and the denial of their means to secure a home.

Schemes of Discrimination

The archive illustrates how policies of racial discrimination in housing were systematically challenged in California, and eventually struck down. But just as was the case with the Richmond Housing Authority, no sooner had a practice been outlawed than the offending parties would concoct schemes to continue their methods of racial exclusion.

For instance, in 1948 the Supreme Court ruled that racial housing covenants could not be enforced in court without running afoul of the Fourteenth Amendment. Later that year, realtors in the East Bay city of Hayward attempted to circumvent this ruling by pushing for property owners to require the approval of a “special corporate committee” to sell, lease, or rent their property. The function of this committee was to deny applications from Black people.

Perhaps the most notorious example of backlash to efforts to secure just housing were the efforts to repeal the 1963 California Fair Housing Act, also known as the Rumford Act. Named after its champion, Assemblymember William Byron Rumford, who was the first Black person elected to state public office in Northern California, the act prohibited racial discrimination in the sale or rental of public housing and most private housing. Notably, this law was passed five years before the federal Civil Rights Act of 1968, which outlawed housing discrimination and aimed to reverse housing segregation.

But white realtors were outraged that they could no longer profit off people’s prejudices, and the next year they organized a campaign to codify their right to discriminate into state law. The California Association of Realtors sponsored Proposition 14, an initiative to nullify the Rumford Act and amend the California Constitution to allow housing discrimination to continue unabated. In response, the ACLU worked with Howard Lewis—the sole member of the association to stand up at their statewide meeting and vote in opposition to the campaign—to convince the public to oppose the measure.

Our initial efforts didn’t work. Arguments for racial justice and fair housing proved less persuasive to the California public than the California Association of Realtors’ message that the Rumford Act was a violation of people’s property rights. Proposition 14 passed with 65% of the vote. A supermajority of Californians chose to create a constitutional right to discriminate.

Thankfully, the proposition never took root. A flurry of civil rights organizations, including the ACLU, challenged it in court, and eventually, in Reitman v. Mulkey, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the measure violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Housing Discrimination’s Ongoing Impact

When viewed through the lens of progress and backlash, the story we like to tell ourselves about our state’s steady march toward progress becomes unsettled. Any victory that was achieved was hard-fought, and not the end of the tale. Discrimination was reinvented or its lasting damage papered over, with consequences that linger today.

California’s policies of housing discrimination prevented the accumulation of generational wealth and was part of the systemic racism that drained Black communities of opportunities and resources. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, Black people are “two times more likely to be earning at low income levels than at high income levels.” White families, by contrast, are more than twice as likely to be earning at the highest income levels. The racial disparities are even greater when you measure wealth instead of income. According to a report by the Federal Reserve Bank, Black households in the L.A. metro area have about 1% of the household wealth as white households.

The impact of housing discrimination is also evident in the racial disparities in our state’s homeless population. Today, U.S. Census data shows that while 6.5% of California is Black, Black people account for 40% of homeless people in the state. In the San Francisco Bay Area, U.S.-born Black residents are three times more likely to live in poverty than white residents. And once forced onto the street, Black people are more at risk of discriminatory and potentially deadly interactions with the police.

In nearly any decade of the ACLU Archive, you can find numerous examples of cities abusing their unhoused residents. In 1994 San Francisco pursued a program to ban homeless people from sleeping in public parks or any public property. The city had 1,400 shelter beds but 11,000-16,000 homeless people, so those who couldn’t find a bed had nowhere to rest or live without being targeted by the police. The result was, as one advocate described it, to “outlaw everything but walking for homeless people.”

Roughly ten years later, the ACLU sued Fresno and CalTrans for their rampant violation of homeless people’s rights. Police regularly conducted sweeps that indiscriminately destroyed people’s life necessities, including wheelchairs, medications, photographs, personal papers, tents, and other crucial items, while providing no alternative shelter for people. In the words of one of our clients, Al Williams, “when the police look at you as a homeless person, they think you have no way of defending yourself legally. I’d stand up and I’d get the gun in my face. You back off and you just watch. You feel helpless.”

The criminalization of the houseless continues to this day. We have seen a recent resurges up and down state: in Chico, in Lancaster, and in Pacifica. Wherever these policies are passed, they cause great harm: attacking people’s dignity, jeopardizing people’s health, and keeping those most in need of support and stability living on a knife’s edge.

You can't separate the current racial disparities in California's housing crisis and homeless population from decades of racist policies and discrimination. The damage that these policies caused has never been addressed – which is why our neighborhoods are so segregated and the racial differences in wealth so stark. Secretary of State Dr. Shirley Weber, the author of AB 3121 which established the Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, has made clear that housing must be central to the conversation:

We need to look at housing patterns. California had some very, very racist housing patterns that existed...We had lots of things embedded in our land ownership that prevented folks from buying or selling homes to African Americans. All of those things are important as we begin to say, [this is] why African Americans continue to struggle, have the least amount of wealth amassed, [and] have low home ownership.

We hope that the ACLU archive can provide additional evidence in support of this vital work. Housing is a human right that has been withheld on racial lines. Our laws and efforts must acknowledge this history, and proactively repair it.

Brady Hirsch is an associate communications strategist at the ACLU of Northern California, where he leverages print and digital media tactics to meet the organization's advocacy goals.